The downside of the no-kill movement

Betty was one of many dogs I met when touring a rural southern part of the country. A volunteer took her out of her cage so we could play with her, but she melted in our arms and just wanted to be comforted. When it was time to go back in her cage, she dragged her whole body, her eyes pleading with us not to make her go back.

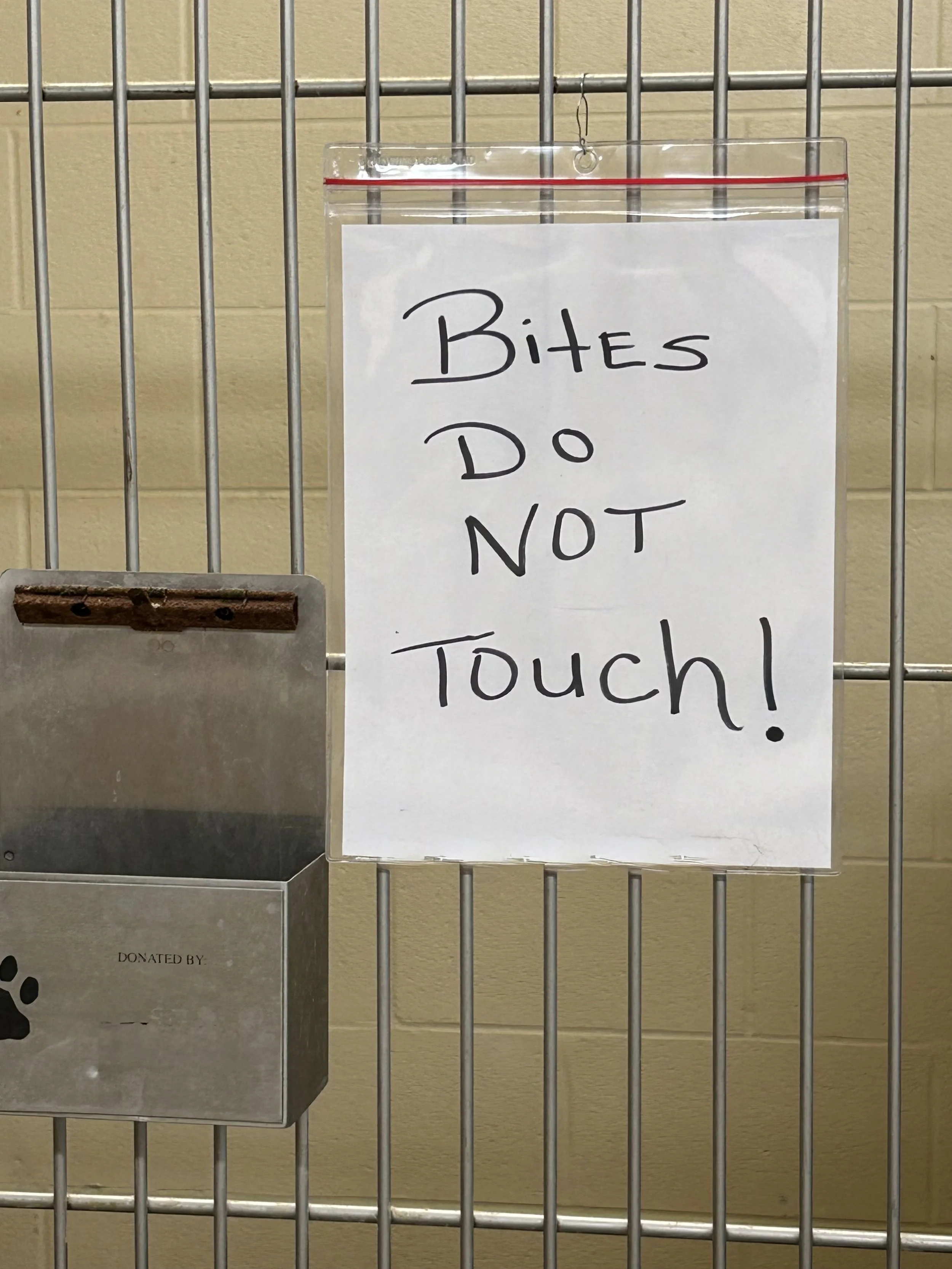

The sign hanging on the cage at the shelter read “Bites – Do Not Touch!”.

The dog was being housed at a shelter in the southern area of the country, an area with a severe dog overpopulation problem.

I wondered what would happen to him. With far more dogs in need of adoption than people adopting in the community, it was unlikely someone would choose him. How long would he live in the shelter cage?

Down the road, another shelter had a sticker on the entrance that told visitors the shelter was “no kill.” The sticker was provided by a large, well-known organization that had provided training to the shelter to help them reduce euthanasia. Next to the sticker was a sign that said intake was closed. The cages were all full.

The shelter wasn’t going to take in more animals, but there were still homeless animals in the community who needed a place to go. What options did they have? Not many.

And what about the animals being housed at the shelter where intake was closed – how long had each dog been living there, what was their daily life like, and how likely was it that they’d get chosen for adoption?

In some cases, “no kill” can also mean selective admission. In other words, some “no kill” shelters pre-screen dogs and only take the more desirable ones. These shelters have a noble goal of not euthanizing as many animals, but at what cost to the animals who aren’t admitted? The hard reality is that someone else has to step in when admissions are limited, and then be criticized for euthanizing. The only other option is leaving animals to fend for themselves on the streets, sometimes in scorching hot or bitter cold temperatures.

I don’t know what kind of staffing resources the “Intake Closed” shelter had, but at some shelters in that area, the dogs don’t get let out of their cages very often for walks or playtime. They are confined to their cage, day after day, week after week, and sometimes, year after year. Some shelters only had the resources to feed the dogs once per day. And on holiday weekends, the dogs had to go days without food. Is that better than being euthanized? I don’t know.

What I do know is that “no kill” is a loaded term, and often doesn’t tell the full story.

We all want every dog to have a good life, and wish there was never a need for euthanasia. But the reality is that we’re a very long way from the day when every dog in need has a home. I’ve worked with organizations that were on both ends of the euthanasia spectrum, and I don’t really know what’s right, or where the line should be drawn. Almost always, shelters, regardless of label, are run by hard-working and passionate staff who are paid very little to do a lot, and want the best for every animal in their care. It’s not their fault there are too many animals in need, not enough options for animals, and not enough people adopting. It’s everyone’s problem to solve.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the topic. Please comment below or email me!